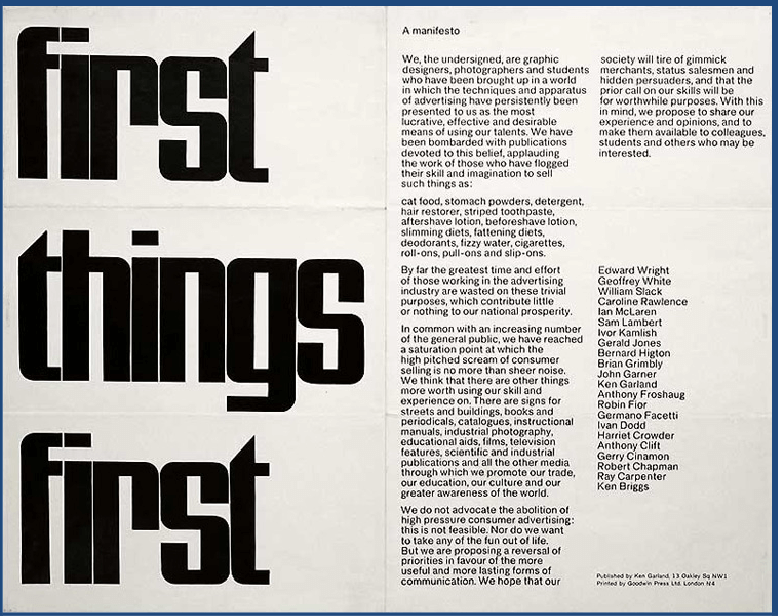

So, if I remember it correctly, I met Ken Garland in 2011 after a lecture he gave at my university. We spoke a bit about the myth of neutrality within design and what he hoped for each of us studying, and also what practices he hoped we’d keep close as we ventured into working life. That afternoon I went home and read his manifesto and general lifework. It struck me shortly after, but I guess I hadn’t internalised it properly yet, that similarly to his manifesto entitled ‘First Things First‘ published in 1964, as a student who was deeply unhappy with the design education I was receiving at the time, that I also had things to say about the conditions of my industry. And I certainly had thoughts about the possibilities of the design school beyond its increasing commercialised output, namely, and to quote his manifesto, that we had “reached a saturation point at which the high pitched scream of consumer selling is no more than sheer noise”. The commercial focus of my design course was setting me up to function and be grateful in precisely the conditions that Garland had previously criticised.

The university I attended prided itself on the strength of its connection to the ‘industry’, our educational modules were modelled after what the industry needed at the time. However, the industry was hugely commercialised by that point. Of course, it had been increasingly so since the mid 60s, meaning that student work took on certain practices that were not instrumental to their understanding of design but instead catered to a capitalist, classist and exclusionary industry (one could argue that this is the crux of design, and that actually it is realistic to preemptively condition people to survive in a system we’re already knee-deep in). The aforementioned conditions, which, by that point had already been ingrained in our education and understanding of the value of design included, but were not limited to; unpaid labour, design as facilitation of current oppressive systems, and the branding and design of products to further mass consumerism. By introducing these themes and major corporate players (i.e Shell, Barclays) into our modules, the institution taught students what kind of life they were to expect post-education.

About a year ago, I worked on a project for a large communications agency with a prominent bank as a client. We’d been working tirelessly to create a visual for an upcoming internal event. We arranged lockups, brainstormed concepts then abandoned them, sketched new forms, rejigged typography and colours to meet a brief against a tight deadline. We worked on multiple revisions until we were left with hundreds of variations of graphics on the office floor. By now, the client had spent upwards of ninety-five thousand Swiss francs and about three months on a design for an in-house event that should not have taken more than a couple of weeks at most. It must have been around 1 am when I was tweaking a design that the client liked that I looked around at my desk, which now housed a dozen visual experiments from the last four hours. I became overwhelmed with the sheer amount of money and time that had gone into a process for which I could not see clear value.

“I felt disillusioned with the design industry, and the thought of doing this for the rest of my life sent a pang of dire to my stomach.”

This event was not the first time (nor will it be the last) that I had been involved in a project like this. So much of my early design education was to do precisely what I was doing. It was a reflection of the standard I was being judged against whilst studying; branding an event, branding a product, making up stories to go with packaging for a can of tuna, fashioning stories to go with a logo for a retail park, all to convince a client or the teacher that the thing they were paying for (or grading) was actually worth what we said it was. Yet earlier on this year, on the cusp of a burn-out I was to have shortly after this project, I felt disillusioned with the design industry, and the thought of doing this for the rest of my life sent a pang of dire to my stomach.

I thought about how I got to where I was—churning out design after design for half a dozen clients a week, and thought that surely at some point, I’d wanted more for my career. Although this was true at my heart’s helm, practically, this was not the trajectory I’d be set on from my student days. Whilst studying, my aspirational compasses were set north to commercial agencies such as BBH, Wieden + Kennedy, Ogilvy, and more. Of course, there were also smaller design studios that were sometimes mentioned and invited for lectures. Still, it seemed apparent that a sliding scale of success was promoted and championed, and smaller businesses and non-white studios stayed at the bottom of it. The quality of student and alumni success could be traced to what industry giant they’d gone on to work for.

“What legacy do we leave students with? More importantly, by making the ‘industry’ central to professional creativity, what kind of designers are we teaching students to be?”

I am presently twofold because I don’t know if this industry-driven drivel was a bad thing for me at the time. As an 18-year-old with a difficult background, attending this university that promised employment in branding and communications (a sector of the industry that tended to pay better and have more jobs) straight after studying felt like the only way to forge a new life for myself. In addition, with rising unemployment rates and astronomical student debt, catering to the industry meant that I was not sitting with a degree that I could not make use of.

Still, I’m curious about the texture of a student’s experience, especially what is required of them to join the workforce. What legacy do we leave students with? More importantly, by making the ‘industry’ central to professional creativity, what kind of designers are we teaching students to be? And what do we say of their creative skills? That they are suitable only for an industry they need to serve? (An industry which the institution has already predetermined as valuable at that?) In my case, the story I initially shared was a remnant of my design education; working in a huge agency was a part of how I saw my talents could be best used. Of course, we can call into question the proper function of design, and many design publications would have you believe that we predominately work on the most inspiring things, but that’s not true at all. A lot of us spend most of our times pitching a project in hopes of landing a client, brushing up old flyers, producing internal powerpoint presentations for people who haven’t yet handed in the content—as well as designing a birthday card for your boss’ wife because…well—he’s sure you can just “squeeze” it in.

I was being overworked in a big agency on projects that I did not find necessary or enriching for the society I lived in, even though I’d been taught that that was what success looked like. This is not to say that every project I do needs to be exciting, culturally relevant, or political. But I have qualms with how much of our work often excludes these themes, even when they touch us so deeply. What I enjoy about my work, especially with what I have been able to achieve outside of my 9-5 job design job, often has less to do with pure aesthetics and more about its functional potential. There is something special that can happen when designers are able to apply their skills to beyond the branding or designing of “cat food, stomach powders, detergent, hair restorer, striped toothpaste, aftershave lotion, beforeshave lotion, slimming diets, fattening diets, deodorants, fizzy water, cigarettes, roll-ons, pull-on and slip-ons”. Instead what does it look like for a design student to consider the ethics of their trade, the implications of a visual language and how they can go into the world and shift the design paradigm?

At this point, I am solely responsible for the trajectory of my career; this is true. I am also responsible for finding joy in my work, this is also true. Nevertheless, it is important to interrogate where my professional trajectories started and what my initial guidances were—were they worthwhile? What practices did I learn that are not actually conducive to my professional or personal development, and what does it mean to recondition my design practice after studying?

—

In Memory of Ken Garland (1929–2021)

Dear Reader,

Thank you for reading thus far. This journal chronicles various personal interests, ranging from design critique to sartorialism and beauty and photography. What ties all these subjects together is the understanding of myself as a consumer and as a designer who sees these things as inspirations of my trade and therefore wants to reflect upon them. the purpose is in the process of journaling, not the polished result. I hope you enjoy it all, and thanks again for stopping by.

Where to start?

Read my first post, ‘Salut, Salut‘ to learn about my blogging history,

or ‘The case against personal branding for designers‘, where I share how the design of this website came about.

Alternatively, I also have an interview with my developer, who made a lot of what you see possible.

Warmest

Sherida

The copyright to this content (photo, text and all related media) belongs solely to me, Sherida Kuffour. Any form of usage without my explicit permission is an infringement of those rights.